I. Introduction

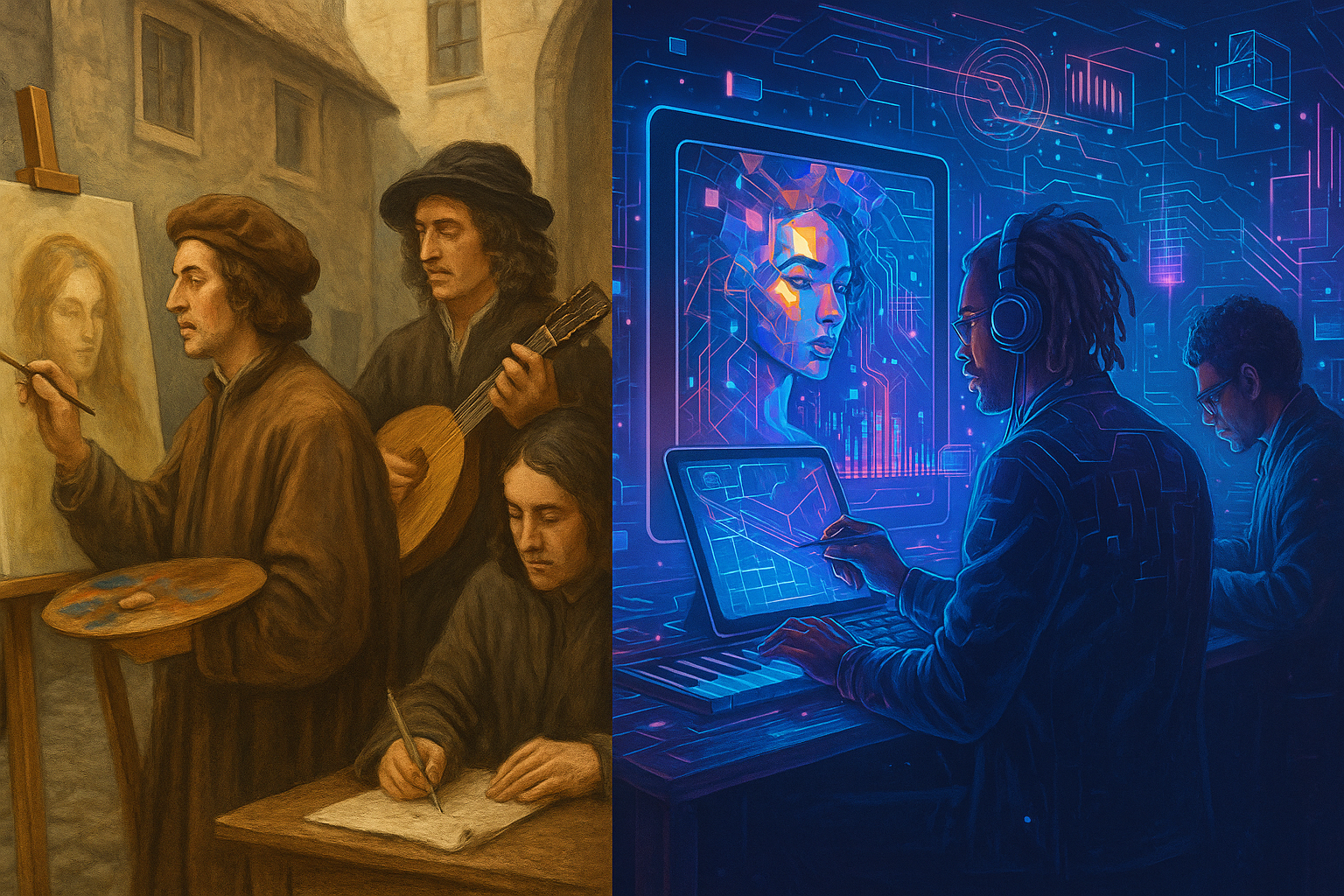

Copyright law protects specific works—not the broader methods, style, or creative identity of their creators. This framework has held for centuries, balancing the competing interests of promoting public access to creative works and ensuring fair compensation to creators.

But does this framework still hold in the age of generative AI?

In Part 1 of this series, we explored how the technological revolution in AI raises the question of whether a legal rebalancing is needed—much like the doctrinal adjustments courts have made in response to the explosion of surveillance technologies under the Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable searches. In Part 2, we challenged the claim that GenAI outputs qualify as “transformative” under the fair use doctrine when the purpose and output of the use is to generate expressive content that competes with—and even threatens to displace—the licensing market for the original copied works.

This final installment asks: Should fair use’s fourth factor—the market harm test—remain confined to the economic impact on the specific work at issue, or should it expand to also account for broader harms at the creator and industry level? And more fundamentally, should courts clarify that the transformative use defense applies only to human-created reinterpretations that advance or are neutral to the original works’ market—and not expanded to automated and mass-generated outputs from AI systems that erode them?

As we explore below, addressing these questions is essential not only to ensure copyright remains a meaningful safeguard for human creativity and the economic survival of creators in the AI-driven creative ecosystem, but also because such an approach is fully consistent with—and well supported by—both statutory law and judicial precedent.

II. Unauthorized AI Training: How It Harms Licensing Markets For Individual Works

Unauthorized AI training undermines two distinct but interconnected markets: the long-established licensing pathways protected by copyright and the nascent but rapidly growing market for AI-specific licenses.

A. The classic licensing harm: Undermining existing revenue streams

Traditional licensing markets lie at the heart of copyright’s incentive and reward structure. Whether excerpts from a book, photos in magazines, songs on soundtracks, illustrations in textbooks, journal articles on research platforms, or film clips in documentaries, creators have long relied on established licensing pathways to monetize and control use of their works. These markets are the backbone of the copyright system’s balance: in exchange for limited exclusive rights, creators are incentivized to bring their works into public view, confident they can control and license uses that would otherwise freeride on their efforts.

But generative AI systems threaten to blow a hole through this familiar ecosystem. When AI developers ingest copyrighted works without permission to train large language models (LLMs), image generators, music generators, or other tools, they are not merely experimenting or doing “research.” Nor are they engaging in commentary, criticism, or scholarship that advances understanding or appreciation of the original works—uses that contribute to the marketplace of ideas that often enhance, rather than erode, the original’s market. Consider the recent Supreme Court decision in Warhol v. Goldsmith.1 In Warhol, the Court emphasized that even where a new use may carry some transformative character, the fourth fair use factor—the effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work—remains critical.2 The Court rejected the idea that any transformative purpose automatically overrides market harm, noting that licensing markets for derivative uses are part of the copyright holder’s legitimate economic interests.3

“Generative AI presents a paradox: it accelerates innovation while simultaneously undermining the ability of individual creators to protect it as intellectual property.”

Rightsholders routinely license their works for uses ranging from textbooks to advertisements, and increasingly, for machine learning applications. When developers skip the step of seeking permission, they directly erode these markets and weaken creators’ ability to negotiate the value o f their contributions in a world where AI systems depend on massive, high-quality datasets.

Courts have repeatedly warned against hypothetical or circular market substitution claims in fair use cases.4 But here, the licensing pathways are concrete, identifiable, and long established.

B. The new frontier: Devaluing the market for AI-specific licenses

Beyond undermining traditional markets, unauthorized AI training threatens an emerging licensing economy: the market for AI training datasets. This is not a hypothetical or artificially constructed market; it is already real and monetized, with major content owners entering licensing agreements to authorize AI model training.

Despite the industry’s general “copy first, ask permission later” ethos (see Part 2 of this article series, here), we now have notable examples of rights holders and AI developers entering into explicit deals. These arrangements reflect growing recognition that licensing works for AI training is not only possible but commercially valuable. For example:

- Media & Publishing: In August 2024, Condé Nast—publisher of The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Wired—signed a licensing deal with OpenAI to allow incorporation of its articles into AI products, with attribution to the original publications.5

- Visual Media: Shutterstock entered a six-year partnership with OpenAI in July 2023, licensing its vast library of images, videos, and music for AI training purposes.6

- Academic & Scholarly Content: Several academic publishers have licensed scholarly content for training large language models. Ithaka S+R maintains a live tracker documenting these agreements.7

- Film & Television: Calliope Networks operates as an aggregator, facilitating licensing deals between AI developers and owners of film and television content.8

[cont’d ↗]

C. IP without teeth is a freeride

These examples demonstrate that the AI-specific licensing market is no hypothetical construct dreamed up in litigation. It already exists and is expanding, driven by industry recognition of legal risks and the value of high-quality, authorized datasets. Courts evaluating fair use claims in the AI context should recognize that bypassing this nascent but legitimate licensing economy causes concrete economic harm. Just as Warhol reinforced the importance of protecting licensing markets for derivative uses, courts should similarly protect the AI-specific licensing market under fair use Factor Four—ensuring that creators’ rights are not eroded simply because technology has outpaced enforcement.

III. Beyond Individual Works: Rethinking Market Harm in the AI Age

Fair use’s fourth factor has traditionally focused on harm to the market for a specific copyrighted work. But generative AI challenges this framing by raising systemic, industry-wide harm—threatening not just individual works but the livelihoods and market standing of creators as a whole—in ways the drafters of the 1976 Copyright Act could not have foreseen.

To understand why, we need to revisit a core principle of copyright law: the distinction between protected expression and unprotected ideas.

A. The “idea-expression” dichotomy or continuum: Where does style properly fall?

Copyright law has long drawn a fundamental line between protected expression and unprotected ideas—a principle enshrined in 17 U.S.C. § 102(b). Under this framework, a creator’s specific arrangement, selection, or coordination of elements in a work is protected, but their general methods, techniques, or artistic style are not.

Courts have repeatedly reaffirmed this idea-expression dichotomy, treating “style” as falling on the idea side of the line and thus free for others to imitate.9

But generative AI challenges whether this clearcut division still holds. These systems do not simply draw inspiration from style in the human sense; they systematically extract, reconstruct, and replicate a creator’s distinctive stylistic fingerprint across entire bodies of work. In doing so, AI exposes the fact that style may not fit neatly into the binary of idea versus expression, but rather operates along a continuum—one where elements traditionally labeled as “unprotected ideas” begin to function as commercially valuable expressive assets.

This raises a critical question: does the rise and application of AI require a reevaluation of where, on the idea-expression spectrum, certain creative attributes should properly fall? General stylistic elements typical of a genre presumably belong in the “idea” category—but are we so sure that an individual artist’s unique style, which can now be systematically deconstructed and replicated at scale, should continue to be treated the same way?

B. AI as a tool for systemic exploitation of creative identity

Generative AI transforms occasional human imitation into systemic machine reproduction. Even if courts continue to treat style as falling on the “idea” side of the idea-expression continuum, AI’s capacity to extract, replicate, and repackage a creator’s distinctive identity at scale fundamentally reshapes the harm analysis under Factor Four: it’s no longer just about substitution for a single work but about erosion of the creator’s ongoing market and livelihood.

Courts have traditionally confined the Factor Four analysis to the specific individual work at issue.10 But AI creates systemic harm. Unlike a human imitator, AI can generate outputs that displace the creator’s future opportunities, including brand deals, adaptations, commissions, appearances. These are not speculative or abstract harms; they reflect real-world economic impacts on the creator’s ability to monetize their reputation, distinctive voice, or artistic identity.

As the Supreme Court reaffirmed in Warhol, licensing markets under Factor Four include both actual and reasonably potential markets the rightsholder might enter.11 Copyright law has evolved in response to technological shifts, such as with the emergence of software as a protectable expressive form.12 It must do so again to address the unique challenges posed by AI. As discussed in Part 1 of this series, copyright law must now grapple with the unprecedented legal questions raised by AI’s capacity to extract value from copyrighted works at systemic scale.

IV. Expressive GenAI Outputs Should Not Qualify for the Transformative Use Defense

While much of the fair use debate in the AI context centers on market harm, solving the problem also requires restoring the transformative use doctrine’s original human-centered purpose.

AI companies frequently claim that training on copyrighted works is “transformative” because it creates something new.13 But the transformative use doctrine was developed to protect human creativity—commentary, parody, criticism—not machine-driven recombination of datasets for automated outputs.

As detailed in Part 2, the Supreme Court in Warhol confirmed that the “purpose and character” inquiry under fair use hinges on whether the use is meaningfully transformative, especially in commercial contexts.14 Using copyrighted works to train AI models should not qualify simply because the machine’s function differs—particularly when the outputs directly compete with human creators.

Just as human authorship is the sine qua non of copyrightability, it is consistent with the logic and purpose of the transformative use defense to apply it only when the secondary use adds new human-authored expression, meaning, or message.15

Courts should clarify that transformative use protects and rewards human reinterpretation—not automated, industrial-scale extraction. Without such recalibration, fair use risks becoming a blanket permission slip for AI companies to monetize copyrighted materials without consent or compensation, eroding the market for the very human creativity that generative AI depends on.

V. Conclusion

Generative AI presents a paradox: it accelerates innovation while simultaneously undermining the ability of individual creators to protect their creative output as intellectual property. But we should not passively accept this erosion of rights. We must honor the constitutional imperative to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts” by recalibrating the balance between public access and private incentive—just as we did when expanding copyright protection to software in the 1980s.16

This debate is not about halting innovation. It is about ensuring that fair use—a doctrine built for human-centered cultural exchange—is not weaponized to systematically strip creators of economic value. Without meaningful adaptation, copyright’s delicate balance risks collapse under industrial-scale AI systems that ingest, remix, and replace human expression.

To preserve that balance, courts should adopt two key clarifications in this incipient AI age:

- Transformative use under fair use (Factor One) should apply only to secondary uses that introduce new, human-authored expression—not to machine-generated outputs that bypass human creativity and directly compete with the original works.

- Fair use’s market harm analysis (Factor Four) should include not only the markets for the original work, including that for use in training AI, which faces clear and measurable harm. It should also account for the harms of the systemic exploitation of creators’ very identity—their distinctive style—which only the rise of AI has made possible.

Courts cannot address these challenges alone. Policymakers, industry leaders, and legal thinkers must develop licensing frameworks and policy tools—whether through updated statutory guidance or collective licensing models—to ensure that AI innovation is matched by innovation in compensating and respecting human creators.

Ultimately, recalibrating fair use for the AI age is not about slowing technological progress. It is about ensuring that progress strengthens and amplifies creativity by the human creators whose work makes it possible, rather than hollowing it out in service of AI or those who control it.

Postscript

The Copyright Office issued just last week its long-awaited report focused on Generative AI Training. Its conclusion was entirely consistent with the analysis in this article series, concluding:

Various uses of copyrighted works in AI training are likely to be transformative. The extent to which they are fair, however, will depend on what works were used, from what source, for what purpose, and with what controls on the outputs—all of which can affect the market. When a model is deployed for purposes such as analysis or research—the types of uses that are critical to international competitiveness—the outputs are unlikely to substitute for expressive works used in training. But making commercial use of vast troves of copyrighted works to produce expressive content that competes with them in existing markets, especially where this is accomplished through illegal access, goes beyond established fair use boundaries.17

But just a few days after publication, the Trump administration fired the U.S. Copyright Office’s Director Shira Perlmutter.18 It is reasonable to expect that the USCO may take on a different policy direction on this and other key copyright and AI legal issues going forward. How these issues will be worked out between the judiciary, the legislature, and the executive branch going forward—in the short, medium, or long term—is anybody’s guess.

© 2025 Ko IP & AI Law PLLC

- Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 598 U.S. 508 (2023) ↩︎

- Id. at 527–28. ↩︎

- Id. at 529. ↩︎

- See Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 590 (1994) (warning against reliance on speculative or hypothetical market harm). ↩︎

- See OpenAI, OpenAI partners with Condé Nast (Aug. 20, 2024), available here. ↩︎

- See Shutterstock, Shutterstock Expands Partnership with OpenAI, Signs New Six-Year Agreement to Provide High-Quality Training Data (July 11, 2023), available here. ↩︎

- See Ithaka S+R, Generative AI Licensing Agreements Tracker (last visited May 25, 2025), available here. ↩︎

- See copyright alliance, Facilitating Efficient and Effective Copyright Licensing for AI

(Jan. 23, 2024), available here. ↩︎ - See Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 348 (1991). ↩︎

- See 17 U.S.C. § 107(4) (“the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work“) (emphasis added); Campbell, 510 U.S. at 590. ↩︎

- 598 U.S. at 535. ↩︎

- See Final Report of the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyrighted Works (1978), the Computer Software Copyright Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-517, § 10, 94 Stat. 3015, 3028 (clarifying that “computer programs” qualify as “literary works” in 17 U.S.C. § 101), and Apple Comput., Inc. v. Franklin Comput. Corp., 714 F.2d 1240, 1249 (3d Cir. 1983). ↩︎

- See Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579. ↩︎

- 598 U.S. at 529. ↩︎

- See U.S. Copyright Office, Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence, 88 Fed. Reg. 16190, 16191–92 (Mar. 16, 2023) (explaining that “only material that is the product of human creativity is eligible for copyright protection” and that “when an AI technology determines the expressive elements of its output, the generated material is not the product of human authorship”), available here. ↩︎

- See supra note 12. ↩︎

- U.S. Copyright Office, Copyright and Artificial Intelligence—Part 3: Generative AI Training, at 107 (May 2025 pre-publication version) (emphasis added), available here. ↩︎

- White House fires head of Copyright Office amid Library of Congress shakeup, Washington Post (May 11, 2025), available here. ↩︎

Leave a Reply